Zen and the Art of Household Maintenance – Ken Cooper

It was while I was holding the shelves my father was fixing to his bedroom wall that I noticed he had aligned the slots on the heads of the screws he was using. They were all horizontal.

“Why do you do that?” I asked.

“Do what?” he said, as he turned the last screw a few degrees anticlockwise to bring the slot in line with the others.

“Line up all the slots on the bracket screws?”

“Why would you not do it?” was his enigmatic reply. Then he said something even more cryptic. “For truth is beauty; beauty truth.” It was the only time I ever heard him say anything about poetry or poets. Suddenly this very practical man about whom I thought I knew everything revealed a side that I’d never seen before. And something made me see how much I’d always taken him for granted. I realised that I loved him very much.

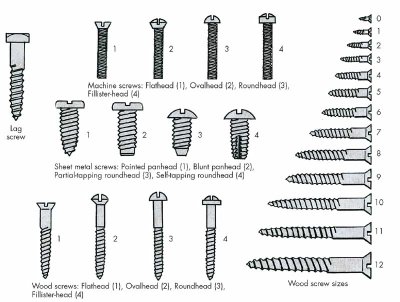

He’d often lectured me about tools – “A bad worker blames his tools. Look after your tools and they’ll look after you.” That sort of thing. He would go on about making sure your cutting tools – chisels, saws, knives – were always sharp. Oh, and “always use the right tool for the job”. And this applied to screwdrivers as much as anything else. The screwdriver must fit the slot properly – not too wide or too narrow, not too thick or too thin. Get it wrong and you’re not maximising the mechanical advantage of the driver, and you’re at risk of tearing the screw head or damaging the surrounding surface.

But he had never said anything about lining up the screws’ slots.

Over the following days I consciously looked for further examples of this practice. The five screws that held the two numerals denoting his house number on the front door – all were aligned vertically. The hinges on the louvre doors of the airing cupboard in his bathroom – eighteen screws whose slots were lined up horizontally. Was it some sort of compulsion; some anal-retentive behaviour? Is that why he never spoke about it? Or was there something I was meant to intuit? I felt like a Shaolin novice, part of whose initiation was to find the answer to the riddle set by the master.

Dad died suddenly two weeks later. A few old friends visited the chapel of rest. Some had been workmates at Chandler’s where Dad was a production engineer. One of the visitors was Uncle Pete. Uncle Pete wasn’t really related, but I’d always called him Uncle. We were just talking – little things he remembered about Dad. He was saying how well thought-of Dad was at Chandler’s. I mentioned the incident with Dad and his lining up of screw slots.

“Ah, well. There’s a reason for that. You see, on the production line, it’s a quick way of checking if everything’s hunky-dory. If all the screws are lined up properly, chances are everything’s adjusted correctly. If you see a screw out of alignment, could mean something’s slipped and needs seeing to.”

“Oh, yes, of course!” I said.

“And,” he added, “It looks neater! ‘Course nobody bothers about that sort of thing anymore. But to your father it was important.”

Now I was beginning to understand the meaning of the fragment of Keats that Dad had quoted. I’d come across a place where Craft meets Art.

Dad’s coffin was made of oak, and I’d gone to the expense of having brass handles fitted. I studied the screws fixing the handles to the coffin.

“Excuse me,” I said to the undertaker, “Do you have a screwdriver I can borrow?”

…ooOoo…